Gnawa music is a Moroccan spiritual musical tradition developed by descendants of enslaved people from sub-Saharan Africa.

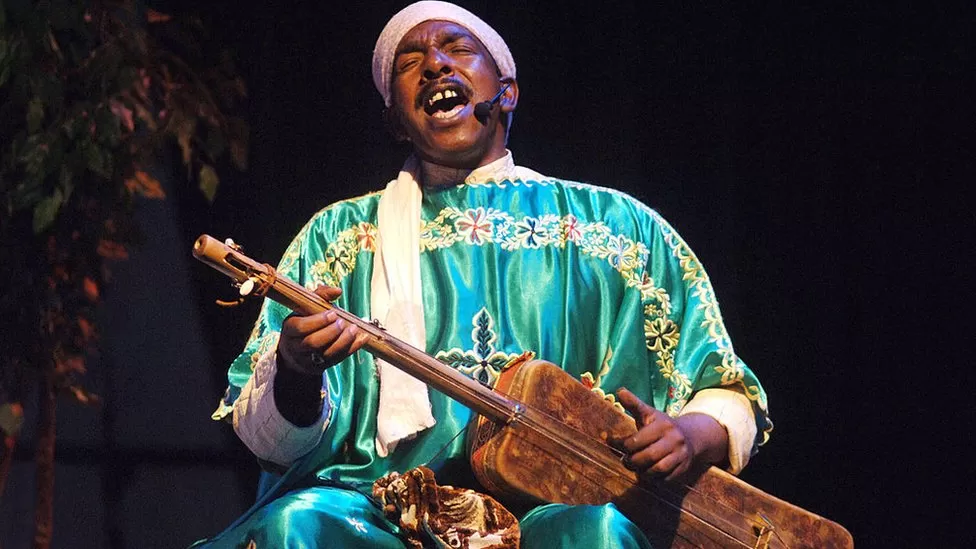

Combining ritual poetry with traditional music and dance, the Gnawa master is centre-stage, playing the main guitar-like instrument, the ghembri.

The Gnawa master was always a man in the deeply patriarchal society, but that changed when Asmâa Hamzaoui came on to the scene.

Her father – a Gnawa master – had hoped to pass the tradition of playing the ghembri to a son. But Rachid al-Hamzaoui only had daughters – including one particularly mischievous but talented one.

And so Hamzaoui ended up breaking the mould. Today, she is a star of Gnawa – long a marginalised culture of street musicians and beggars that is now acquiring a growing following in Morocco, and around the world.

She made her stage debut in 2012 at the annual Gnawa music festival in the southern coastal town of Essaouira – the cultural heartland of the Gnawa people.

“It was a huge responsibility. First, because of the instrument – it was my father’s. I needed to play the same good songs he had taught me. I needed to play them correctly,” Hamzaoui said, as she headlined again at this year’s festival.

“And it was scary – the first time a woman on the stage, playing Gnawa music, representing women.”

There are no records of the number of Gnawa people in Morocco, but their history can be traced back to at least the 16th Century slave trade.

In 2019, the UN cultural agency Unesco listed their culture and music as an “Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity”.

“Gnawa is first and foremost a Sufi brotherhood music combined with lyrics with a generally religious content, invoking ancestors and spirits,” Unesco says.

It says that Gnawa culture is now considered part of Morocco’s multifaceted culture and identity.

“The Gnawa, especially in the city, practise a therapeutic possession ritual through all-night rhythm and trance ceremonies combining ancestral African practices, Arab-Muslim influences and native Berber cultural performances,” Unesco adds.

While the increasing role of women seems largely welcome, even among the community’s elders, their main concern is how the growing popularity of Gnawa music and culture is leading many young artists to seek fame and fortune on the festival circuit, moving away from the spiritual asceticism at the core of the community’s ethos.

One such elder is Naji al-Sudani who creates drums and much sought-after ghembris in his inconspicuous shop. His legendary status in Gnawa circles is confirmed by the continuous stream of people who come to his tiny establishment to sit with him and receive his blessings ahead of their performance.

As his name indicates, his heritage can be traced to Sudan. The name of another legendary Gnawa master, Mahmood Guinea, hints at modern-day Guinea.

“Having women performers could be a good thing, but the main issue for the youth in general is humility – modesty, understanding the culture of transmission from elders and respecting it,” said Sudani, who holds the title of maâlem, master musician.

“The thing is, you cannot say you are a maâlem just because you have a title. You become a maâlem over the years, through learning from the masters,” he added.

But the economic realities of contemporary Morocco means that some, including Hamzaoui, want the music to free them of financial hardship, not just lift them spiritually.

“There’s just me and my sister that carry this home for our parents. We pay their bills and we have to pay ours. I have a son and a lot of things to pay,” Hamzaoui said.

In recent years, the festival in Essaouira, which began purely with a focus on Gnawa music, has evolved to showcase fusions with other genres.

Renowned African-American musician Suleiman Hakim has been coming to the festival since it began in 1998.

Hailing from the American jazz and blues tradition, he says he recognised many of the core sounds in his genre as having a shared origin with Gnawa music.

“That’s part of why it lends itself so well to fusions, because there is something in both the Gnawa sounds and other African-derived sounds which speaks to a shared heritage and history,” he said.

The festival attracts a varied audience, from Gnawa purists to curious tourists.

This year, popular Moroccan actor and singer Fehd Benchemsi performed with his band the Lallas.

“The festival has changed a lot over the years but many of us still come to connect with the Gnawa masters – Essaouira is the heart of Gnawa culture,” he said.

“Coming here is like a pilgrimage of sorts – for some it’s deeply spiritual, for others, it’s more focused on the celebratory aspects of song and dance.”

Benchemsi is not alone – an increasing number of young Moroccans, not born into Gnawa culture, are embracing it, drawn to the festivities and music, but also to its more esoteric spiritual dimension.

It reflects a recognition of Morocco’s links to sub-Saharan Africa and the celebration of a culture of a community that had long been marginalised in a society where Arabs wield the most influence.

Source : BBC

Add Comment